Menu

Slide

doslider02

doslider01

Im mniej, tym więcej

Less is more

Je weniger, desto mehr

Kurator | curator | Kurator: Jerzy Olek

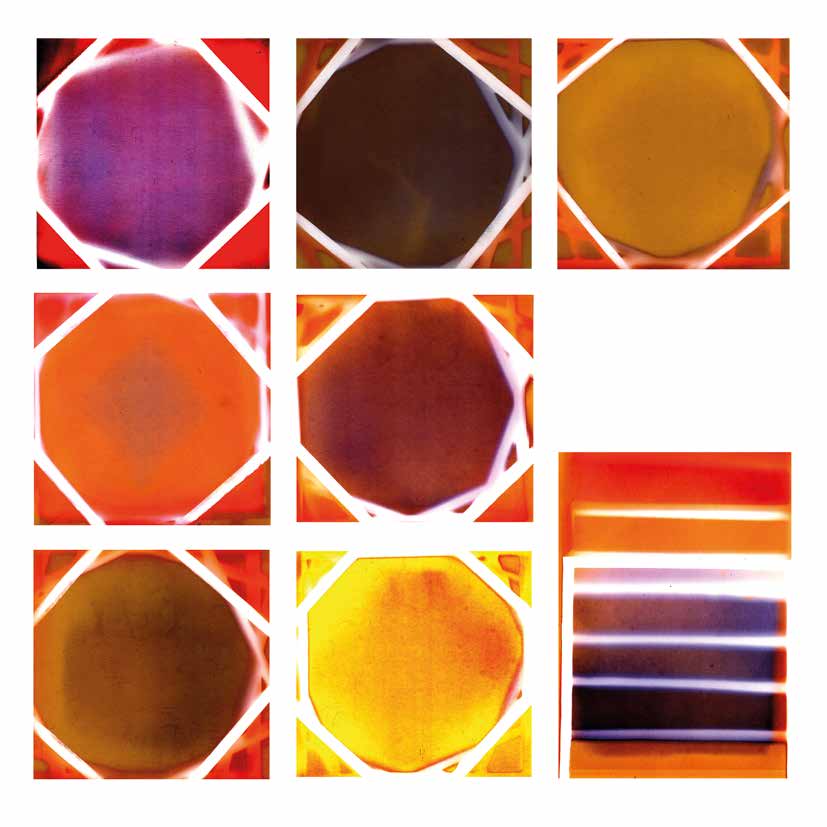

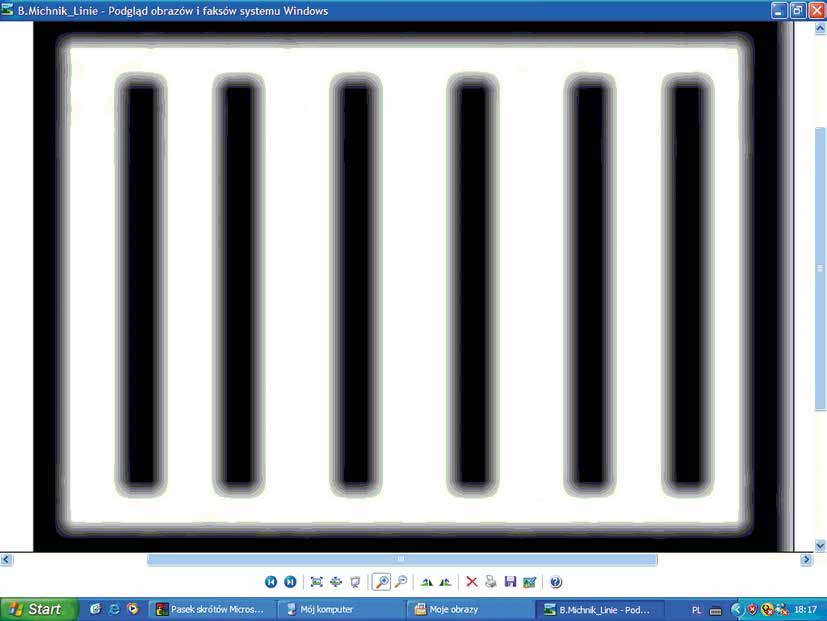

Autor | artist | Autor: Štěpán Grygar (1955), Michał Jakubowicz (1977),Timo Kahlen (1966), Wolf Kahlen (1940), Mirosław Koch (1962), Michael Kurzwelly (1963), Bogusław Michnik (1945),Jürgen O. Olbrich (1955), Jerzy Olek (1943), Anna Panek-Kusz (1975), Marek Poźniak (1960), Marek Radke (1952),Carola Ruf (1955), Marcin Ryczek (1982), Tadeusz Sawa-Borysławski (1952), Zdeněk Stuchlík (1950), Gisela Weimann (1943)

miejsce | place | Ort: Słubicki Miejski Ośrodek Kultury SMOK, ul. 1 Maja 1, Słubice

Mniej przedmiotów

to więcej wolności

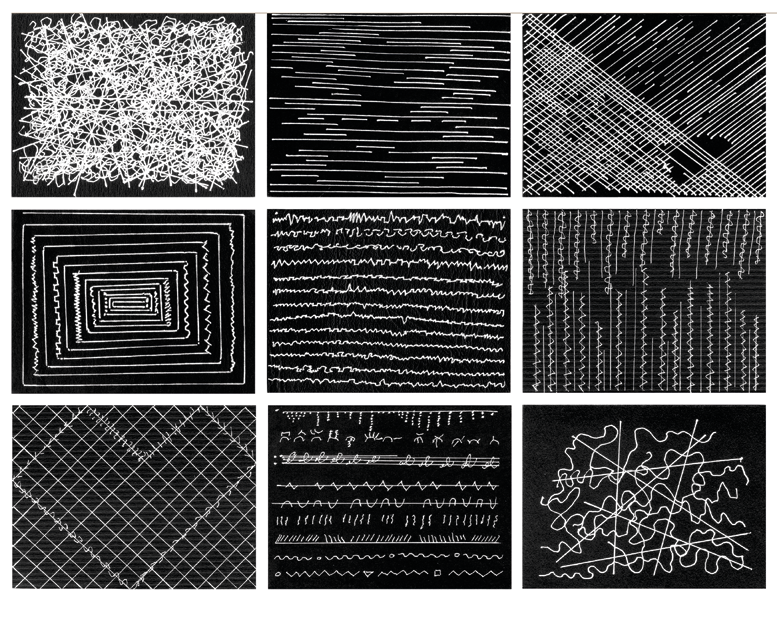

Minimalizm uchodzi za jedną z najbardziej nośnych tendencji sztuki współczesnej. Intryguje surowością formy i prostotą przesłania. W wizualnych wypowiedziach ogranicza się do form najprostszych: figur i brył skrajnie elementarnych. Są to obiekty znane każdemu dzięki swojej oczywistej konstrukcji.

Prostota formy w twórczości minimalistów oraz lapidarność ich wypowiedzi sygnalizują potrzebę ładu i surowej estetyki przeciwstawiającej się dookolnemu chaosowi. Minimal w sztuce to w pewnym sensie zmaterializowanie szeroko pojętej postawy filozoficznej. Skojarzenia mogą być znacznie bogatsze i rysować się wielorako. Mogą się łączyć z:

• minimalistyczną filozofią,

• samoograniczaniem współbycia w zen,

• klasztorną regułą zakonu minimów.

Wystawa ma pokazać egzystujące w sztuce porządki kulturowe i alternatywne wobec nich narracje. Skojarzenia z tytułowym hasłem mogą być jeszcze innego rodzaju: mianowicie sprzeciwianiem się

minimalizowaniu postrzegania, które do rzeczywistości ma odnosić się szeroko i krytycznie. Przykładem bogatej w przejawach twórczości jest dorobek Roberta Morrisa. Minimalizm, w przypadku jego autorskiego

artykułowania, wymyka się jednoznacznym definicjom i klarownym słowom. W wynurzeniach teoretycznych Morrisa, bardziej zresztą niż w dziełach, intryguje mnie podjęcie próby pojęciowego opanowania przestrzeni i relacyjnego odbioru osadzonych w niej obiektów. Obiektów

najprostszych, o maksymalnie oszczędnej formie, spełniających warunki gestaltu, a więc przybierających taką postać, jaka nie daje się sprowadzić do cech swoich części składowych.

Zapytałem Roberta Morrisa, czy jego poglądy z lat 60. są nadal aktualne. Do jakiego stopnia?

R.M.: Na tyle, na ile są gestalty – to znaczy przypadki, kiedy nasze postrzeganie daje nam całość nieredukowalną do sumy części.

J.O.: Do jakiego stopnia można redukować formę kosztem refleksji intelektualnej?

R.M.: Nigdy nie stosowałem takiej redukcji.

J.O.: Jak czuje się pan w roli klasyka minimal artu obecnie, w czasach powrotu idei i wystaw w stylu After Minimal oraz ogólnej dekonstrukcji kultury i filozofii?

R.M.: Wystawy minimalizmu robi się od 40 lat. Nie odczuwam tutaj powrotu idei. O jakiej „dekonstrukcji kultury i filozofii” pan mówi? Wittgenstein? Derrida? Filozofia analityczna? Kontynentalna?

Morris odpowiada tak oszczędnie, jak oszczędna jest jego sztuka. Ale dokąd da się pójść w tę stronę? Twórca terminu „minimal art”, Richard Wollheim, w opublikowanym w1965 roku artykule stawia

pytania o to, „jak dalece można posuwać

się w odzieraniu dzieła z sensów i estetycznych aspektów, żeby pozostało to niezbywalne minimum”.

Jerzy Olek

Less objects

– more freedom

Minimalism is considered to be one of the most resonant contemporary art forms. Intriguing is its austerity in form and simplicity in message. Its visual statements are limited to the simplest forms: figures and extremely elementary solids. Objects familiar to everyone because of their recognizable construction. The simplicity of form in the work of the

minimalists and the conciseness of their statements signal the need for order and a strict aesthetic opposed to the surrounding chaos. Minimalism in art is, in a sense, the materialisation of a broadly

philosophical stance with rich and widereaching connections that can be linked to:

• minimalist philosophy,

• the self-limitation in Zen,

• the monastic rule of the Minimalist Order.

The exhibition aims to show underlying cultural codes in art and how their narratives could be countered. Yet, associations regarding the exhibition title could also be of another kind: namely, a critique of limited, narrow-minded perceptions, as reality should be perceived broadly and critically. The oeuvre of Robert Morris manifests a rich example of work. However, his artistic version of Minimalism escapes

clear definitions and lucid words. What intrigues me in Morris’s theoretical effusions, more so than in his works, is his attempt to conceptualise space and the relational perception of the objects embedded in it. His objects are as simple as possible, with a maximally parsimonious form, yet they meet the requirements of gestalt, meaning that their form cannotbe reduced to the qualities of its constituent parts.

I asked Robert Morris if his views from the 1960s are still relevant today? And to what extent?

R.M.: To the extent that they are gestalts – that is, instances where our perceptions give us a whole irreducible to the sum of its parts.

J.O.: To what extent can form be reduced at the expense of intellectual reflection?

R.M.: I have never applied such a reduction.

J.O.: How do you feel about your role as a classicist of minimal art today, at a time when ideas and exhibitions in the style of

“After Minimal” return and a general deconstruction of culture and philosophy is under way?

R.M.: Minimalism has been exhibited for 40 years. I don’t see a return of ideas here. What ‘deconstruction of culture and philosophy’ are you talking about? Wittgenstein? Derrida? Analytical or continental philosophy??

Morris answers as parsimoniously as his art is parsimonious. But how much further can one go in this direction? Richard

Wollheim, who created the term “minimal art”, asks in an article published in 1965 the question “how far one can go

in stripping a work of its meanings and aesthetic aspects, so that the inalienable minimum remains”.

Jerzy Olek

Weniger Gegenstände

bedeuten mehr Freiheit

Der Minimalismus gilt als eine der bedeutendsten Strömungen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst. Er besticht durch klare Formen und inhaltliche Einfachheit. Im Visuellen beschränkt er sich auf die elementaren Grundformen von Figuren und Körpern. Dabei handelt es sich um Gegenstände, die aufgrund ihrer offensichtlichen Konstruktion jedem vertraut sind. Die Einfachheit der Formen im Werk der Minimalisten und die Prägnanz ihrer Aussagen signalisieren das Bedürfnis nach Ordnung und einer strengen Ästhetik, die sich dem umgebenden Chaos entgegenstellt. ‚Minimal‘ in der Kunst ist in gewisser Weise die Materialisierung einer im weitesten Sinne philosophischen Haltung, die vielfältige Einflüsse und Querverbindungen aufweist bis hinein in die

• minimalistische Philosophie,

• die Selbstbeschränkung im Zen,

• die monastischen Regeln des Minimiten-Ordens.

Die Ausstellung will in der Kunst existierende kulturelle Codes, und mögliche Alternativen zu diesem Narrativ aufzeigen. Doch der Ausstellungstitel könnte auch anderes verstanden werden: Zum

Beispiel als eine Aufforderung sich einer verengten Sicht entgegenzustellen, die doch eigentlich umfassend und kritisch

die Wirklichkeit erfassen sollte. Beispielhaft in seinem künstlerischen

Schaffen ist dafür das Oeuvre von Robert Morris. In seinem Fall entzieht sich der Minimalismus einer klaren Definition und eindeutigen Worten.

Was mich an Morris‘ theoretischen Ergüssen mehr als an seinen Werken fasziniert, ist der Versuch, den Raum und die relationale Wahrnehmung der darin eingebetteten Objekte zu konzeptualisieren. Einfachste Objekte, mit maximal reduzierter Form, die dennoch die Kriterien

einer Figur erfüllen und so gestaltet sind, dass sie nicht auf die Eigenschaften ihrer Bestandteile reduziert werden können.

Ich habe Robert Morris gefragt, ob seine Ansichten aus den 1960er Jahren heute noch aktuell sind? Und in welchem Umfang?

R.M.: In dem Maße, in dem es sich um Formen oder Fälle handelt, die wir als ein nicht auf die Summe seiner Bestandteile reduzierbares Ganzes wahrnehmen.

J.O.: Wieweit kann die Form auf Kosten der intellektuellen Reflexion reduziert werden?

R.M.: Ich habe nie eine solche Verkürzung vorgenommen.

J.O.: Wie empfinden Sie Ihre Rolle als Klassiker der Minimal Art heute, in einer Zeit, in der Ideen und Ausstellungen wie After Minimal zurückkehren und man eine allgemeine Dekonstruktion von Kultur und Philosophie konstatieren muss?

R.M.: Minimalismus-Ausstellungen gibt es seit 40 Jahren. Ich sehe hier keine Rückkehr von Ideen. Von welcher „Dekonstruktion von Kultur und Philosophie“ sprechen Sie? Wittgenstein? Derrida? Analytische oder kontinentale Philosophie?

Morris antwortet genauso sparsam, wie seine Kunst sparsam ist. Aber wie weit kann man in dieser Richtung gehen? Der Schöpfer des Begriffs „Minimal Art“, Richard Wollheim, wirft in einem 1965 veröffentlichten Artikel die Frage auf, „wie weit man gehen kann, um ein Werk von seinen Bedeutungen und ästhetischen Aspekten zu befreien, so dass das unveräußerliche Minimum übrigbleibt“.

Jerzy Olek

Krótka

chora

historia

sztuki

post mortem

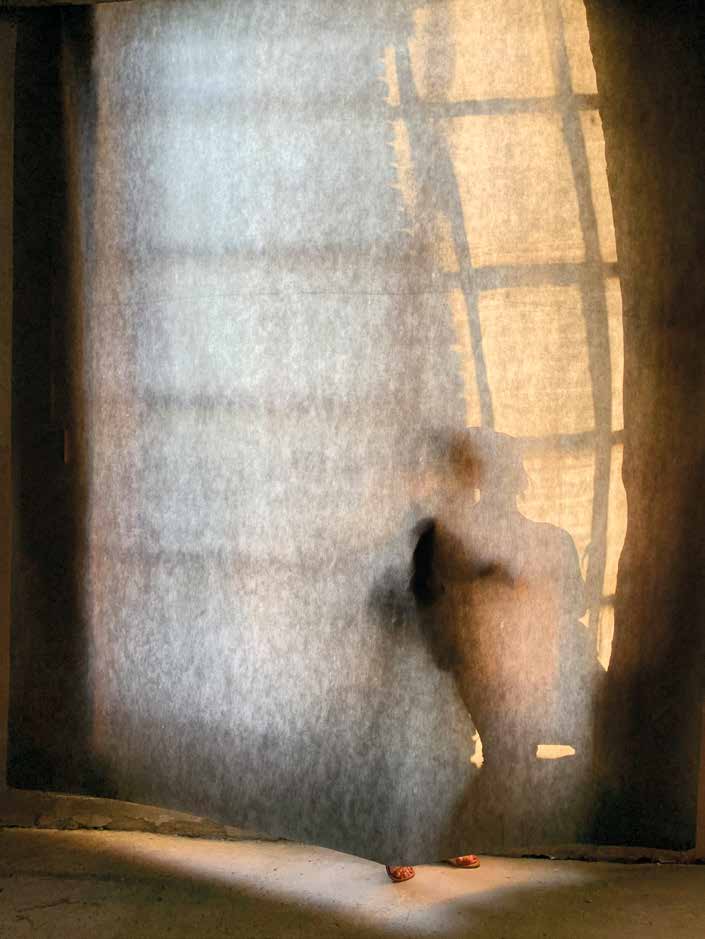

Budzę się gwałtownie ze snu. Każdy koszmar ma swój koniec, wracamy do porządku dziennego. Nie zamierzam już nigdy więcej zapisywać

żadnego z moich cud-ownych snów, traci się tylko na to cały poranek. Ale chociaż jeszcze ten jeden. Jest krótki. Mój przyjaciel Wojciech Bruszewski (WB) ma wystawę w jednej z europejskich stolic (zapomniałem jakiej). Pomagam mu. Zgrabny, elokwentny dyrektor muzeum z precyzyjnie przyciętą (turecką) fryzurą i lokiem w stylu okresu burzy i naporu (Sturm und Drang) jest zestresowany i codziennie pyta WB, czy nie potrzebuje pomocy. Sala jest już przygotowana, ale jeszcze jest w niej pusto. WB go uspokaja (a także siebie samego).

W dniu otwarcia wystawy sala w dalszym ciągu jest jeszcze pusta. Przed żelazną bramą wejściową (podobną do tej na zamku Charlottenburg w Berlinie) gromadzi się grupa zamożnych ludzi. On (WB) wyjmuje z kieszeni mały, splątany kłębek niebieskiej nici i podchodzi do wschodniej bramy zamku. Bierze kłębek nici i wciska go w (oczywiście pustą) dziurkę od klucza. Wszystkie oczy skierowane są na zamek. Nikt nie mówi ani słowa. Wtedy ja (a potem wszyscy) odkrywam w szczelinach kostki brukowej ścinki papieru z (częściowo) czytelnymi słowami. Jedno

z nich brzmi: rzeź. WB prosi teraz wszystkich, aby poszli do (małej) pobliskiej restauracji na rogu. Stoją tam 1922 miniaturowe stoliki. Na każdym z nich jest miejsce tylko na jedną łyżeczkę. Gospodarz serwuje na każdej (łyżeczce) rulonik szynki wieprzowej z (igiełką) rozmarynu. Wszyscy są zachwyceni jej delikatnym smakiem. „W końcu jakaś sztuka do przekąszenia!”.

Budzę się, patrzę na zegar i widzę: 6 września. Tego dnia 13 lat temu, w 2009 roku, WB zmarł. (Po wszystkim stwierdzam, że zapisanie tego

naprawdę nie było takie złe, jak myślałem.)

Berlin, 6 września 2022

Wolf Kahlen

Short

sick

art

history

post mortem

Abruptly, I wake up from a dream. Like all nightmares this one also has an end and we get back to business as usual. I don’t really intend to ever again write down one of my wonder-ful dreams. It would take me all morning. Just this one. It’s a short one. My friend Wojciech Bruszewski (WB) has an important show in a European capital (forgot in which one). I help him. The sleek, eloquent museum’s director with a precisely parted (Turkish) haircut and a hair curl storming to the upper left is nervous and asks every day if he (WB) needs a hand assuring him that the exhibition space is prepared, blank and empty. He (WB) reassures him (and himself). Yet, on the opening day the exhibition space is still totally empty. An army of well-to-does gather in front of a wrought iron gate (similar to the one at Charlottenburg Castle in Berlin). He (WB) takes from his pocket a small tangled ball of blue thread and walks up to the Castle’s eastern gate. He takes the thread ball and presses it into the gate’s (naturally empty) key hole. All eyes are directed to the castle. Nobody says a word.

Then I discover (and after me everybody else) that in the cracks between the cobble stones, there are little pieces of paper with (partly) intelligible words written on them. One of them bears the word: bloodbath.

Now he (WB) invites us all into a (small) corner restaurant nearby. Here, there are 1922 miniature tables. They are so small only a table spoon fits on each of them. The chef places on each (table spoon) a roll of pork ham with a (needle of) rosemary. We are happy about the fine taste. ‘Finally, art to devour!’ I wake up, look at my watch and see, it is September 6th.

On this very day he (WB) had died in 2009, sixteen years ago. (After all, writing this down wasn’t as bad as I had feared.)

Berlin, September 6th, 2022

Wolf Kahlen

Kurz

Kotz

Kunst-

geschichte

post mortem

Ich wache abrupt auf aus einem Traum. Wie alle Albträume hat er ein Ende, und wir gehen zur Tagesordnung über. Ich habe nun wirklich nicht vor, jemals wieder einen meiner wunder-baren Träume aufzuschreiben, dann ist ja der halbe Vormittag hin.

Diesen aber. Ist ja kurz. Mein Freund Wojciech Bruszewski (WB) hat

eine repräsentative Ausstellung in einer europäischen Hauptstadt (ich hab vergessen, welcher). Ich helfe ihm. Der aalglatte, eloquente

Museumsdirektor mit dem (türkischen) präzisgescheitelten Haarschnitt mit der Sturm- und Drang-Haarwelle nach links oben ist nervös und fragt täglich, ob er (WB) Hilfe brauche, der Saal sei schon vorbereitet, aber noch spiegelblank leer. Er (WB) beruhigt (auch sich selber).

Am Tag der Eröffnung ist der Saal immer noch leer. Die Heerschar der Betuchlichen versammelt sich am schmiedeeisernen Portal des

Museums. (So einem wie an unserem Charlottenburger Schloss in Berlin). Er (WB) zieht aus seiner Hosentasche ein kleines Bündel (verwickelten) blauen Fadens und geht zum Schloss (des Portals) an der Ostseite. Er nimmt die Schnur und drückst sie in das (natürlich leere)

Schlüsselloch. Aller Augen sind auf das Schloss gerichtet, keiner sagt ein Wort. Da entdecke ich (und danach ein jeder) zwischen den Pflastersteinen rundherum in deren Ritzen überall Papierfetzen mit (teils) leserlichen Wörtern. Auf einem steht: Blutbad.

Er (WB) bittet nun alle ins (kleine) nahegelegene Eckrestaurant. Dort stehen 1922 Miniaturtischchen. Auf jedem hat nur ein Teelöffel

Platz. Der Wirt serviert auf jedem (Teelöffel) ein heiss gebackenes Röllchen Schweineschinken mit Rosmarin(nadeln) drauf. Alle sind beglückt über den feinen Geschmack. ‚Endlich mal wieder Kunst zum Verdauen‘. Ich wache auf, sehe auf die Uhr und sehe: 6. September.

An diesem Tag im Jahr 2009 war er (WB) gestorben, vor 13 Jahren.

(Das Aufschreiben war doch nun wirklich nicht so schlimm, wie ich befürchtet habe)

Berlin, 6. September 2022

Wolf Kahlen

Nie nic

W greckim systemie liczbowym litera „O” (omikron) oznacza liczbę 15, zgodnie z jej pozycją w alfabecie greckim. Podobnie łaciński system liczbowy wykazuje bezpośredni związek między liczbą i literą.

Rozłożone „U” tworzące „O” to papierowy obiekt autorstwa Caroli Ruf, który w zabawny sposób łączy w sobie słowo i liczbę. Zarówno matematycznie, jak i symbolicznie liczba zero reprezentuje „zbiór pusty”, który nie jest niczym, co odpowiada niemieckiemu „czarnemu zeru” (hamulcowi zadłużenia) reprezentowanemu w finansach.

Not Nothing

According to the alphabetic Greek numerals the letter O (omicron) stands for the number 15, corresponding to its position in the Greek alphabet. Similar to the Latin numeral system it displays a direct

connection between number and letter. Unfolding the U to form an O, Carola Ruf’s paper object playfully links term and number.

Both mathematically and symbolically, the number zero represents an “empty set”, which is not nothing, something the German “black zero” (to be in the black) supposedly represents in finance.

Nicht nichts

Im griechischen thesischen Zahlensystem steht der Buchstabe O (Omikron) für die Zahl 15, entsprechend seiner Stellung im griechischen Alphabet, also eine unmittelbare Verbindung zwischen Zahl und Buchstabe ähnlich dem lateinischen Zahlensystem.

Mit dem aufgeklappten U zum O werden bei dem Papierobjekt von Carola Ruf Begriff und Zahl spielerisch in Verbindung gebracht.

Die Null als Zahl stellt sowohl mathematisch als auch symbolisch eine „leere Menge“ dar, also nicht nichts, was die deutsche „schwarze Null“ angeblich auch im Finanzwesen zum Ausdruck bringen soll.

Filozofowie, badacze sztuki, artyści, architekci, kuratorzy, dietetycy, socjologowie, ekonomiści, menedżerowie, politycy i wielu innych od wieków zastanawiają się nad odpowiednimi „mniej” i „więcej” w życiu i kulturze: formułują traktaty, opracowują zasady estetyczne i wymyślają style artystyczne, piszą prace doktorskie, zakładają partie polityczne, stają się sławni i potężni, wszczynają wojny, tłumią myślących inaczej, otrzymują tytuły profesorskie, publikują teksty w katalogach, wygłaszają mowy inauguracyjne, dają wskazówki dotyczące zdrowego odżywiania… i spierają się, nazywając się nawzajem awangardystami lub konserwatystami, mają rację lub nie, odnoszą sukcesy lub porażki, są wybierani na stanowiska lub z nich odwoływani…

For centuries male and female philosophers, art scholars, artists, architects, curators, nutritionists, sociologists, economists, managers, politicians and many others have been thinking about the right ‘less’ and ‘more’ in life and culture. They formulate treatises, develop aesthetic guidelines and invent art styles, write doctoral theses, found political parties, become famous and powerful, start wars of conquest, oppress dissenters, get professorial titles, publish texts in catalogues, give opening speeches, devise guidelines for healthy nutrition … The have arguments, call each other either avant-garde or regressive, see each other as right or wrong, are successful or not, are elected or voted out of office …

Über das richtige ‘Weniger’ und ‘Mehr’ in Leben und Kultur denken Philosoph:innen, Kunstwissenschaftler:innen, Künstler:innen,

Architekt:innen, Kurator:innen, Ernährungswissenschaftler:innen, Soziolog:innen, Betriebswissenschaftler:innen, Manager:innen,

Politiker:innen und viele Andere seit Jahrhunderten nach, formulieren Traktate, entwickeln ästhetische Richtlinien und erfinden Kunstststile, schreiben Doktorarbeiten, gründen politische Parteien, werden berühmt und mächtig, beginnen Eroberungskriege, unterdrücken Andersdenkende, bekommen Professorentitel, veröffentlichen Texte in Katalogen, halten Eröffnungsreden, geben Richtlinien für gesunde Ernährung … und streiten sich, bezeichnen sich gegenseitig entweder als avantgardistisch oder rückschrittlich, richtig oder falsch denkend, haben entweder Erfolg damit oder nicht, werden

gewählt oder abgewählt…